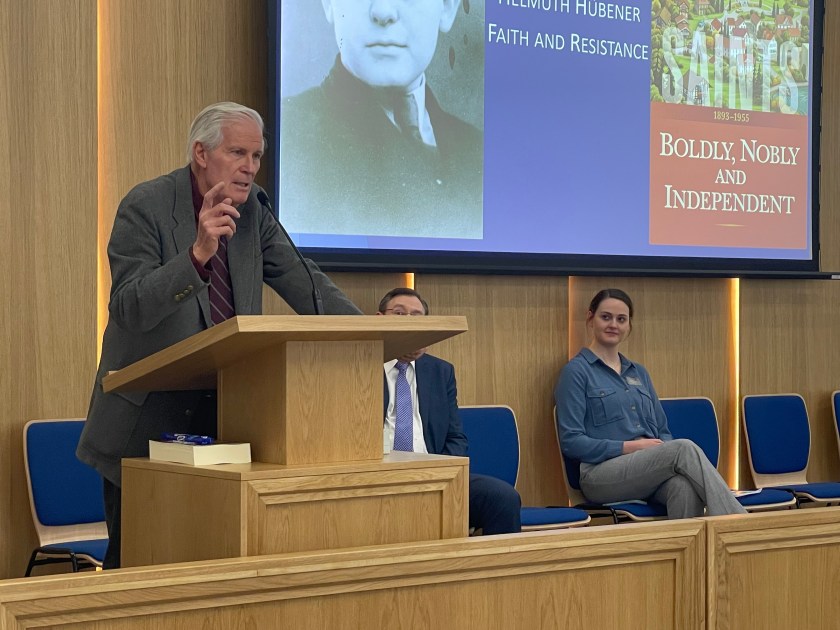

Today we had a very special “Lunch and Learn” at work. Our friend, Alan Keele is on a 5-6 week tour of Germany, speaking about Helmuth Hubener, who’s 100th birthday was on 8 January 2025. We thought it would be nice to have him speak to all of us, so we helped to make that happen here. Alan is a dear friend–we were back fence neighbors years ago in Orem.

Christian Fingerle, head of the Church History Department here with 3 members of Helmuth Hubener’s step-brother’s family:

Ralf Grünke introduced Alan and the other participants.

First we had a reading from SAINTS, vol. 3. where Helmuth’s story is beautifully told (see below).

Then Alan, author of several publications about Helmuth, spoke to us about his experiences uncovering this story and sharing it with the world.

He started by telling the Grimm’s Fairytale of The Emperor’s New Clothes:

I think this lunch lecture was impactful and made us all stop and wonder what we’d have done had we been there then. It’s a very important question. I want to be better at standing for truth and righteousness.

Here’s Helmuth Hubener’s Story:

SAINTS

Chapter 27

God Is at the Helm

“Come to my house tonight. I want you to hear something,” sixteen-year-old Helmuth Hübener whispered to his friend Karl-Heinz Schnibbe. It was a Sunday evening in the summer of 1941, and the young men were attending sacrament meeting with their branch in Hamburg, Germany.

Seventeen-year-old Karl-Heinz had many friends in the branch, but he particularly enjoyed spending time with Helmuth. He was smart and confident—so intelligent that Karl-Heinz had nicknamed him “the professor.” His testimony and commitment to the Church were strong, and he could answer questions about the gospel with ease. Since his mother worked long hours, Helmuth lived with his grandparents, who were also members of the branch. His stepfather was a zealous Nazi, and Helmuth did not like being around him.1

That night, Karl-Heinz quietly entered Helmuth’s apartment and found his friend hunched over a radio. “It has shortwave,” Helmuth said. Most German families had cheaper radios provided by the Nazi government, with fewer channels and limited reception. But Helmuth’s older brother, a soldier in the German army, had brought this high-quality radio home from France after Nazi forces conquered the country in the first year of the war.2

“What can you hear on it?” asked Karl-Heinz. “France?”

“Yes,” Helmuth said, “and England too.”

“Are you crazy?” Karl-Heinz said. He knew Helmuth was interested in current events and politics, but listening to enemy radio broadcasts during wartime could get a person thrown in jail or even executed.3

Helmuth handed Karl-Heinz a document he had written, filled with news about the military successes of Great Britain and the Soviet Union.

“Where did you get this?” Karl-Heinz asked after reading the paper. “It can’t be possible. It is completely the opposite of our military broadcasts.”

Helmuth answered by switching off the light and turning on the radio, keeping the volume down low. The German army worked constantly to jam Allied signals, but Helmuth had rigged up an antenna, allowing the boys to hear forbidden broadcasts all the way from Great Britain.

As the clock struck ten, a voice crackled in the dark: “The BBC London presents the news in German.”4 The program discussed a recent German offensive in the Soviet Union. Nazi papers had reported the campaign as a triumph, without acknowledging German losses. The British spoke frankly of both Allied and Axis casualties.

“I’m convinced they’re telling the truth and we’re lying,” Helmuth said. “Our news reports sound like a lot of boasting—a lot of propaganda.”

Karl-Heinz was astonished. Helmuth had often said that Nazis could not be trusted. He had even engaged in political discussions on the subject with adults at church. But Karl-Heinz had been reluctant to believe his teenage friend over the words of government officials.

Now it seemed that Helmuth had been right.5

One Sunday evening, back in Germany, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe and Rudi Wobbe waited for Helmuth Hübener to arrive for sacrament meeting at the Hamburg Branch.13 For the past few months both Karl-Heinz and fifteen-year-old Rudi had been helping Helmuth distribute anti-Nazi flyers around the city. As a branch clerk, Helmuth had the branch typewriter at his house so he could write letters to Latter-day Saint soldiers, and he often used it to produce the flyers, which had bold headlines like “They Are Not Telling You Everything” or “Hitler, the Murderer!”14

Distributing the flyers was high treason, a crime punishable by death, but the young men had so far evaded the authorities. Helmuth’s absence from church was troubling, however. Karl-Heinz wondered if perhaps his friend was sick. The meeting went on as usual until branch president Arthur Zander, a member of the Nazi Party, asked the congregation to remain in their seats after the closing prayer.

“A member of our branch, Helmuth Hübener, has been arrested by the Gestapo,” President Zander said. “My information is very sketchy, but I know that it is political. That is all.”15

Karl-Heinz locked eyes with Rudi. The Saints seated near them were whispering in astonishment. Whether they agreed with Hitler or not, many of them believed it was their duty to respect the government and its laws.16 And they knew any open opposition to the Nazis from a branch member, however heroic or well intentioned, could put them all in danger.

On the way home, Karl-Heinz’s parents wondered aloud what Helmuth could possibly have done. Karl-Heinz said nothing. He, Rudi, and Helmuth had made a pact that if one of them should get arrested, that person would take all the blame and not name the others. Karl-Heinz trusted that Helmuth would honor their pact, but he was afraid. The Gestapo had a reputation for torturing prisoners to get the information they wanted.17

Two days later, Karl-Heinz was at work when he answered a knock at the door. Two Gestapo agents in long leather overcoats showed him their badges.

“Are you Karl-Heinz Schnibbe?” one of them asked.

Karl-Heinz said yes.

“Come with us,” they said, leading him to a black Mercedes. Karl-Heinz soon found himself squeezed in the back seat between two agents as they drove to his apartment. He tried to avoid incriminating himself as they questioned him.

When they finally arrived at his home, Karl-Heinz was grateful that his father was at work and his mother at the dentist. The agents searched the apartment for an hour, flipping through books and peering under beds, but Karl-Heinz had been careful not to bring any evidence home. They found nothing.

But they did not let him go. Instead, they put him back inside the car. “If you lie,” one of the agents said, “we will beat you to a pulp.”18

That evening, Karl-Heinz arrived at a prison on the outskirts of Hamburg. After he was shown to his cell, an officer with a nightstick and pistol opened the door.

“Why are you here?” the officer demanded.

Karl-Heinz said he didn’t know.

The officer hit him in the face with his key ring. “Do you know now?” he yelled.

“No sir,” Karl-Heinz answered, terrified. “I mean, yes sir!”

The officer beat him again, and this time Karl-Heinz gave in to the pain. “I allegedly listened to an enemy broadcast,” he said.19

That night Karl-Heinz hoped for peace and quiet, but the officers would not stop throwing open the door, turning on the lights, and forcing him to run to the wall and recite his name. When they finally left him in darkness, his eyes burned with fatigue. But he could not sleep. He thought of his parents and how worried they must be. Did they have any idea he was now a prisoner?

Weary in body and soul, Karl-Heinz turned his face to his pillow and wept.20

A few months later, in a prison in Hamburg, Germany, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe waited to stand trial for treason. Shortly after his arrest, he had seen his friend Helmuth Hübener in a long, white holding room with dozens of other prisoners. The prisoners had all been ordered to keep their noses to the wall, but as Karl-Heinz walked past, his friend tilted his head, grinned, and gave a little wink. Helmuth, it seemed, had not incriminated him. The young man’s bruised, swollen face suggested that he had been beaten severely for holding out.26

Not long after that, Karl-Heinz also saw his friend Rudi Wobbe in the holding room. All three boys from the branch had been arrested.

During the first few months of his imprisonment, Karl-Heinz endured interrogation, threats, and beatings at the hands of the Gestapo. The interrogators could not imagine that Helmuth Hübener, a seventeen-year-old boy, could be behind such a conspiracy, and they demanded to know the names of the adults involved. Of course, there were no adult names to offer.27

On the morning of August 11, 1942, Karl-Heinz changed from his prison uniform into a suit and tie sent from home. The suit hung on his thin frame like it might on a hanger in the closet. Then he was brought to the People’s Court, infamous in Nazi Germany for trying political prisoners and handing down terrible punishments. That day, Karl-Heinz, Helmuth, and Rudi would stand trial for conspiracy, treason, and aiding and abetting the enemy.28

In the courtroom, the defendants sat on a raised platform facing the judges, who were draped in red robes adorned with a golden eagle. For hours, Karl-Heinz listened as witnesses and Gestapo agents detailed evidence of the boys’ conspiracy. Helmuth’s flyers, full of language denouncing Hitler and exposing Nazi falsehoods, were read aloud. The judges were enraged.29

At first, the court focused on Karl-Heinz, Rudi, and another young man who had been one of Helmuth’s coworkers. Then they turned their attention to Helmuth himself, who did not appear intimidated by the judges.

“Why did you do what you did?” one judge asked.

“Because I wanted people to know the truth,” Helmuth replied. He told the judges that he did not think Germany could win the war. The courtroom exploded in anger and disbelief.30

When it was time to announce the verdict, Karl-Heinz was shaking as the judges returned to the bench. The chief judge called them “traitors” and “scum.” He said, “Vermin like you must be exterminated.”

Then he turned to Helmuth and sentenced him to death for high treason and aiding and abetting the enemy. The room fell silent. “Oh no!” a visitor to the courtroom whispered. “The death penalty for the lad?”31

The court sentenced Karl-Heinz to five years in prison and Rudi to ten. The boys were stunned. The judges asked if they had anything to say.

“You kill me for no reason at all,” Helmuth said. “I haven’t committed any crime. All I’ve done is tell the truth. Now it’s my turn, but your turn will come.”

That afternoon, Karl-Heinz saw Helmuth one last time. At first, they shook hands, but then Karl-Heinz wrapped his friend in an embrace. Helmuth’s large eyes filled with tears.

“Goodbye,” he said.32

The day after the Nazis executed Helmuth Hübener, Marie Sommerfeld learned about it in the newspaper. She was a member of Helmuth’s branch. He and her son Arthur had been friends, and Helmuth had thought of her as a second mother. She could not believe he was gone.33

She still remembered him as a child, bright and full of potential. “You will yet hear something really great about me,” he told her once. Marie did not think Helmuth was boasting when he said it. He had simply wanted to use his intelligence to do something meaningful in the world.34

Eight months earlier, Marie had heard about Helmuth’s arrest even before the branch president’s announcement over the pulpit. It had been a Friday, the day that she normally helped Wilhelmina Sudrow, Helmuth’s grandmother, clean the church. When she entered the chapel, Marie had seen Wilhelmina kneeling before the pulpit, her arms outstretched, pleading with God.

“What is the matter?” Marie had asked.

“Something terrible has happened,” Wilhelmina replied. She then described how Gestapo officers had shown up at her door with Helmuth, searched the apartment, and carried away some of his papers, his radio, and the branch typewriter.35

Horrified by what Wilhelmina was telling her, Marie had immediately thought of her son Arthur, who had recently been drafted into the Nazi labor service in Berlin. Could he have been involved in Helmuth’s plan before he left?

As soon as she could, Marie had traveled to Berlin to ask Arthur if he had participated in any way. She was relieved to learn that, although he had occasionally listened to Helmuth’s radio, he had no idea that Helmuth and the other boys were distributing anti-Nazi materials.36

Some branch members had prayed for Helmuth throughout his imprisonment. Others were angry at the young men for putting them and other German Saints in harm’s way and jeopardizing the Church’s ability to hold meetings in Hamburg. Even Church members who were not sympathetic to the Nazis worried that Helmuth had put them all at risk of prison or worse, especially since the Gestapo were convinced that Helmuth had received help from adults.37

Branch president Arthur Zander believed he had to act quickly to protect the members of his branch and prove that Latter-day Saints were not conspiring against the government. Not long after the boys’ arrest, he and the interim mission president, Anthon Huck, had excommunicated Helmuth. The district president and some branch members had been angered by the action. Helmuth’s grandparents were devastated.38

A few days after Helmuth’s execution, Marie received a letter he had written to her a few hours before his death. “My Father in Heaven knows that I have done nothing wrong,” he told her. “I know that God lives, and He will be the proper judge of this matter.”

“Until our happy reunion in that better world,” he wrote, “I remain your friend and brother in the gospel.”39

———-

President Smith had since thrown his energies into alleviating suffering, injustice, and hardship. He arranged for the first printing of the Book of Mormon in braille and organized the first Church branch for the deaf. After learning that Helmuth Hübener, the young German Saint executed by the Nazis, had been wrongly excommunicated from the Church, he and his counselors reversed the action and directed local authorities to note this fact on Helmuth’s membership record.

——————–

Taking Alan to the Bahnhof this afternoon:

Dr Keele was an incredible professor and one of my favorites at BYU. We loved his passion for German and all that encompassed ♥️

LikeLike