This is the Judengasse Museum in Frankfurt. You can read more about our visit last January in this post. It is a must see museum, fascinating.

This afternoon we took the kids to visit the Jewish Cemetery behind the Judengasse Museum. It’s closed on Saturdays, so we’ve never been able to visit there until today. You have to go into the Museum and leave collateral to get the key to the cemetery, which is always locked. We were the only ones there and we were instructed to lock the gate in the wall behind us when we entered.

The Jewish Cemetery was outside the old Frankfurt wall (which the Ghetto backed up to). It was inclosed with a high wall. The grass was not mowed, there were big chestnut and oak trees, moss covered the old stones. It was peaceful and very old. The cemetery had been partially destroyed. There were piles of broken stones.

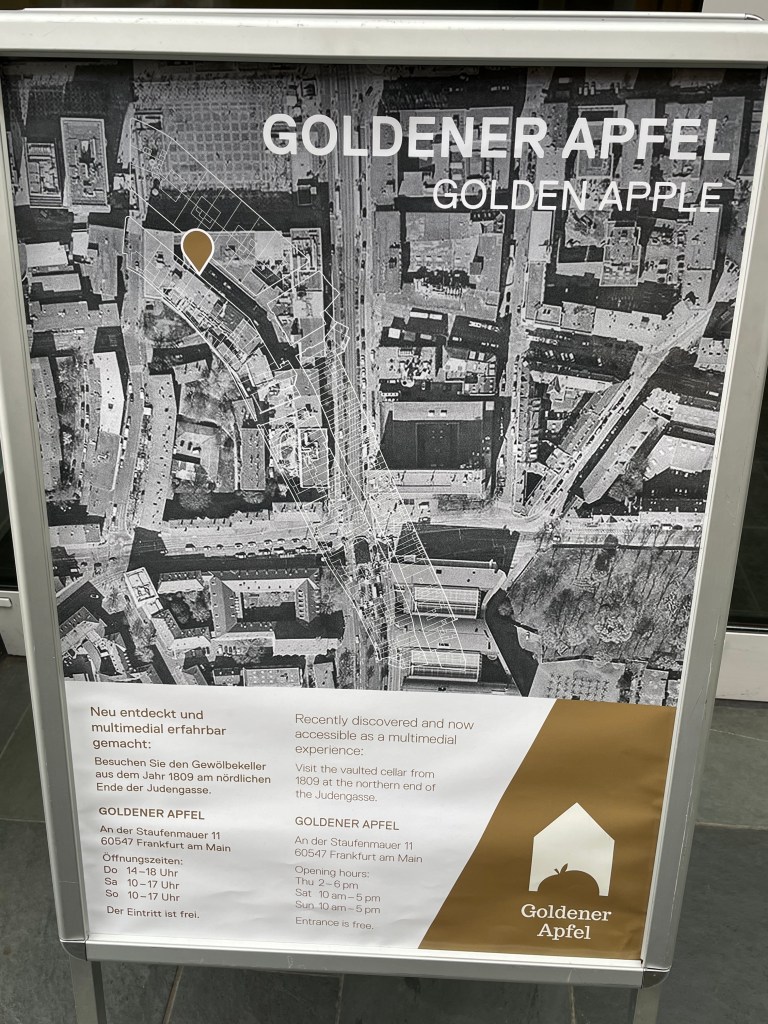

You can see the location of the Jewish ghetto in the overlay on the photo below.

The location of the cemetery is marked below:

The sign said this is the oldest preserved Jewish burying place of the city of Frankfurt, and the earliest provable burials. The oldest stone is for Hanna bat Alexander, died in 1272 and the last is 1828.

The cemetery was almost completely destroyed 1938-1942. In 1995, the outer wall was redesigned to be a memorial, with stone markers embedded all the way around memorializing the Jews who died during WWII.

Here is some good information about this sacred place:

Old Jewish Cemetery on Battonnstrasse

https://www.juedischesmuseum.de/en/visit/old-jewish-cemetery-frankfurt/

800 Years of Jewish History

Overview

The Jewish Cemetery on Battonnstrasse lies tucked away under a dense canopy of treetops in the southeast section of Frankfurt’s inner city. It is the second oldest preserved Jewish cemetery north of the Alps after the “Heiliger Sand” (Holy Sand) Jewish Cemetery in Worms, Germany. The oldest extant tombstone dates back to 1272–the oldest material evidence of Jewish life in Frankfurt.

The cemetery originally lay outside the city and was not included within the city walls until the city was expanded in 1333. Jewish communities of the surrounding areas that did not have their own cemetery also laid their dead to rest there until the 16th century. This hallowed ground served Frankfurt Jews as a final resting place until 1828. When Frankfurt’s new Main Cemetery was established, the Jewish community was also allotted a new cemetery on the south-eastern boundary of the new Main Cemetery, on Rat-Beil-Strasse. In 1929, a new Jewish cemetery was created flanking the north of the Main Cemetery, on Eckenheimer Landstrasse. It is still used for interment today.

Expropriation and Destruction

In 1939, the Jewish community was forced to sell their cemeteries along with their other properties to the City of Frankfurt. The plan was to level the Battonnstrasse cemetery. Demolishment of the almost 6,500 gravestones commenced at the beginning of 1943. Some 175 selected tombstones, of historical importance or particular value in an artistic sense, were removed in advance to the cemetery on Rat-Beil-Strasse. The demolition work on the cemetery was halted due to bombings and debris and rubble dumped there instead. As a result, 2,500 tombstones remained fully preserved, along with thousands of shattered tombstone fragments.

Presentation by the Lord Mayor to the city councillors, December 23, 1942

“The old Jewish cemetery on Dominikanerplatz is to be cleared as soon as possible and prepared for use as a dumping ground should there be major building damage caused by enemy air raids. […] The costs for removing some 7,000 tombstones and part of the trees amount to approximately RM 35,000.”

Jewish Community Frankfurt

The cemetery was returned to the newly formed Jewish Community after the end of Nazi rule. However the clean-up work on the cemetery continued until the end of the 1950s. The tombstones that had been removed to Rat-Beil-Strasse were returned and stacked up along the inside of the cemetery wall, as their original location could no longer be determined. The tombstones of some well-known personalities such as Mayer Amschel Rothschild and Rabbi Nathan Adler were grouped together in a corner at the southern wall. Between 1991 and 1999, the cemetery was pictorially and textually documented. Images of the tombstones and their epitaphs along with translations and commentaries have been published on the website of the Salomon Ludwig Steinheim Institute in Essen.

Many of the gravestones in the cemetery bear images such as a rabbit, a windmill, or a fish trap. The houses in the Judengasse didn’t have house numbers. The marks on the gravestones show in which house on the Judengasse the deceased lived.

Visiting these old sacred places always causes me to pause and consider the eternities and God’s plan for each of us. I am grateful that all things will be restored, bone, skin, flesh and even stone.